In The Life of Ernest

Ernest served with the 5th Canadian Mounted Rifles (Quebec Regiment). They served as a mounted infantry unit of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) during the first world war. In 1916, they converted to an infantry battalion associated with the 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade, 3rd Canadian Division.

The mounted rifles saw action in the theatre of France, and received battle honours for many pivotal battles, including Somme, Ypres, Passchendaele, Vimy, and Canal du Nord.

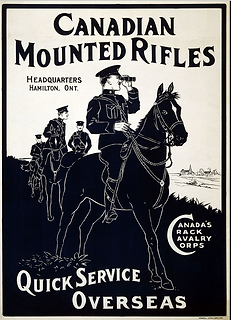

A poster advertising the Canadian Mounted Rifles. A heroic, respectable figure is pictured with the phrase "Quick Service Overseas" underneath. Enticing to eligible recruits through their lust for glory and a quick, supposedly easy job.

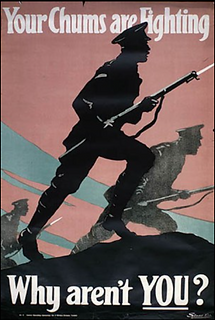

Propaganda , enticing men to enlist. This particular piece plays on a man's sense of guilt, utilizing the phrase: " Your chums are fighting why aren't you". This gives men a feeling of duty to serve, to help their friends overseas, and to support the war effort. The poster feature soldier in silhouette to add to the unanimous factor; those soldiers could be anyone.

Two Fictional Letters from Ernest and his Mother

Dearest Mum,

How are things? Sorry I haven't written, but the trenches are so vile and wet, anything and everything soon becomes soaked. Don't panic, but I'm in the hospital. It's nothing really, just a gunshot wound to my knee, and the nurses think I'll be back fighting fritz soon.

I'm not quite sure where exactly I am, but I know that I am far from the front line, that's for certain.

Mum, the war isn't what they said it was. It's cold all of the time, and we can never truly sleep. It's not much better in hospital. Some men, those awake, scream. They awake and cry out in agony. I feel ashamed, lying in bed with an injury likewise to a splinter, compared to what some of these men have. I do believe these images will haunt me forever.

The battle itself is another nightmarish massacre. No man's land is a hellscape only the suicidal or insane enter. It's a graveyard littered with shell holes, dead horses, and the bloated, yellowing carcases of both friend and foe. I still remember when I was a greenhorn and was out to work collecting bodies. Some died from gas, others shot, others we had to scrape from the earth after they had a close encounter with a shell. Lord, the stench. It clung too you as if it were the dead themselves grasping at life, choking you as you pass. Sorry to drone on Mum, but I need to talk. The men don't listen, not that they would want to. Sometimes I don't know who's eyes are more lifeless; the dead or the living.

I'll try to write again, if not, know that I love you and Da, always. P.S. How's Hilda? Every time I send a letter to her address in Peterborough, it gets returned.

Love, Ernie

Dearest Ernest,

Da sends his love, he's been working so hard to help the war efforts. I believe that Hilda has moved to Bridgnorth ONT. Try sending it to the P.O [Post Office] there.

I wish I could be there with you, we all do. We all miss you so much! Hilda has been working tirelessly at General Electric in Peterborough to fill in for the men fighting. We all have been making shells, farming, or knitting for you brave soldiers. Speaking of which, I just sent five pairs [socks] to you. I do hope you get them before you re enter combat. As well, a and I saved some money for you, and bought some cigarettes and had duplicates of photos made for you.

We love you Ernie, and we all wish for you to return to us safe and sound.

Love from all, Mum

Ernest King

Ernest King was born in Norwich England April 16, 1894, where his mother and father resided at 81 Muriel Road. Ernest was a smaller, fair skinned man, who worked as a carpenter. He had no previous military training, but that didn’t stop him from enlisting in Peterborough September of 1915. It is unclear if Ernest was living in Peterborough in 1915, or if he was visiting, however during the war, he had a wife, a Mrs. Hilda King whom resided in Peterborough at 312 Townsend st, and later Bridgnorth. Hilda is not listed as his next of kin on his attestation papers, or even as a wife for that matter, however she is listed as his dependent, and is written a death notice. Thusly, we can assume they were married between September 1915, and October 1917.

Private King embarked from Halifax of the SS Empress of Britain on July 15, 1916, and arrived in Liverpool 15 days later. This ocean liner would carry thousands of Canadian soldiers to fight throughout the war. He served with his fellow Peterborough brethren with the 93rd battalion, and later was transferred to the 5th Canadian Mounted Rifles (Quebec Regiment) Throughout his service, he fought valiantly in many gruesome battles, including the battle of Somme, and Passchendaele.

The battle of the Somme took place in the theater of France along the western front. Lasting from the summer to the fall of 1916, Canadian troops fought a grueling fight against Fritz. Originally holding down a section of the front in Belgium, in late August, the Canadians shifted towards the Somme front near the French village of Courcelette. They were immediately faced with fire, and suffered 2 600 casualties. It was here, where the Canadians developed new tactics to reclaim areas from the enemy, such as the creeping barrage, and newly developed tank warfare. Ernest was wounded October 10,1916 at Somme. He received a gunshot wound just below the knee, and was hospitalized for 39 days at Springburn-Woodside Red Cross General Hospital, Glasgow. The hospital, originally a cooking school, was converted to a red cross hospital in wartime. Afterwards, he returned to the front to fight. Ernest was lucky, as over 24 000 Canadians were injured, killed, or were never found after Somme.

A year after his first injury, Ernest died on Oct 30, 1917 at Passchendaele. By the time the Canadians arrived, British and American troops had been fighting an unsuccessful battle for three months, with 100 000 casualties for little ground won. By October 26, we’d gained ground on the ridge, but still faced heavy fire from the German forces. On October 30, fresh battalions replaced the exhausted troops, and the battle continued. Heavy losses were suffered as the Canadians gained more ground. Ernest was shot in the back, and died alongside 82 of his fellow members of the 5th Canadian Mounted Rifles. The Canadians went on to help secure the victory after three months of fighting in the cold, wet, waterlogged massacre that was Passchendaele.

Private King was buried at the Nine Elms British Cemetery in Belgium, where he still lies today. He is commemorated in both the Peterborough, and the national book of remembrance, however he is not listed at the Peterborough cenotaph, or the memorial in Bridgnorth. He is not listed on the digitized file for the Norwich memorial.

In Loving Memory of Pte. Ernest King

I Died in Hell (They Call it Passchendaele)

Fifth Business

"The battle was the most terrible of my experience; we were trying to take a village that was already a ruin, and we counted our advances in feet; the front was a confused mess because it had rained every day for four weeks and the mud was so dangerous that we dared not make a forward move without the laborious business of putting down duckboards, lifting them as we advanced, and putting them down again ahead of us; understandably this was so slow and exposed that that we could not do much of it. I learned from later reading that our total advance was a little less than two miles; it might have been two hundred. The great terror was the mud. The German bombardment churned it up so that it was horribly treacherous, and if a man sank in much over his knees his chances of getting out were poor; a shell exploding nearby could cause an upheaval that overwhelmed him, and the likelihood even of recovering his body was small." (Davies, 69)

"How long I crawled I do not know, for I was by this time more frightened, muddled, and desperate than ever before or since. 'Disorientation' is the word now fashionable for my condition. Quite soon I was worse than that; I was wounded, and so far as I could tell, seriously. It was shrapnel, a fragment of an exploding shell, and it hit me in the left leg, though where I cannot say; I have been in a car accident in later life, and the effect was rather like that-a sudden shock like a blow from a club; and it was little time before I knew that my left leg was in trouble, though I could not tell how bad it was." (Davies, 72)

The novel Fifth Business by Peterborough author Robertson Davies, features the protagonist, Dunny, growing up in a small town, and, among other great events in his life, serving in the first world war. Dunny serves at the battle of Passchendaele, where he is severely wounded and taken to a hospital in England.

Ernest King was just one of the many soldiers from Peterborough who died at Passchendaele. Robertson Davies may have been inspired from the mass number of soldiers from Peterborough who fought there to feature it in his book instead of another battle.

Squire nagged and bullied till I went to fight,

(Under Lord Derby’s Scheme). I died in hell—

(They called it Passchendaele). My wound was slight,

And I was hobbling back; and then a shell

Burst slick upon the duck-boards: so I fell

Into the bottomless mud, and lost the light.

At sermon-time, while Squire is in his pew,

He gives my gilded name a thoughtful stare:

For, though low down upon the list, I’m there;

‘In proud and glorious memory’ ... that’s my due.

Two bleeding years I fought in France, for Squire:

I suffered anguish that he’s never guessed.

Once I came home on leave: and then went west...

What greater glory could a man desire?

Siegfried Sassoon, Written on memorial tablet

Music:

Fiddler's Green

The Tragically Hip

The song describes a place in Irish folklore that you go when you die before your time. It's a place where you may live at peace until your loved ones arrive to take you to the afterlife, a place of peace.